3D Printing and Sustainable Building Materials

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has flourished over the past 40 years, creating a means for widely accessible small-scale manufacturing at an affordable price. The first commercial 3D printing technology, the Stereolithography Apparatus machine, was invented by Charles Hull in 1984 (Liu et al. [1]). Successfully patented and commercialized in 1986, the machine relied on ultraviolet lasers to cure liquid photopolymer resin, thus building 3D objects layer by layer. Since then, pressure by activists, consumers and politicians has encouraged corporations to create more environmentally conscious ways to 3D print, expanding the technology to encompass the fields of medicine, architecture, manufacturing, aerospace engineering and even fashion. Anticipated to grow from a $19.33 billion industry in 2024 to over $101.74 billion in 2032 according to Fortune Business Insights, 3D printing represents the future of construction and the potential for sustainable building and design (“3D Printing”).

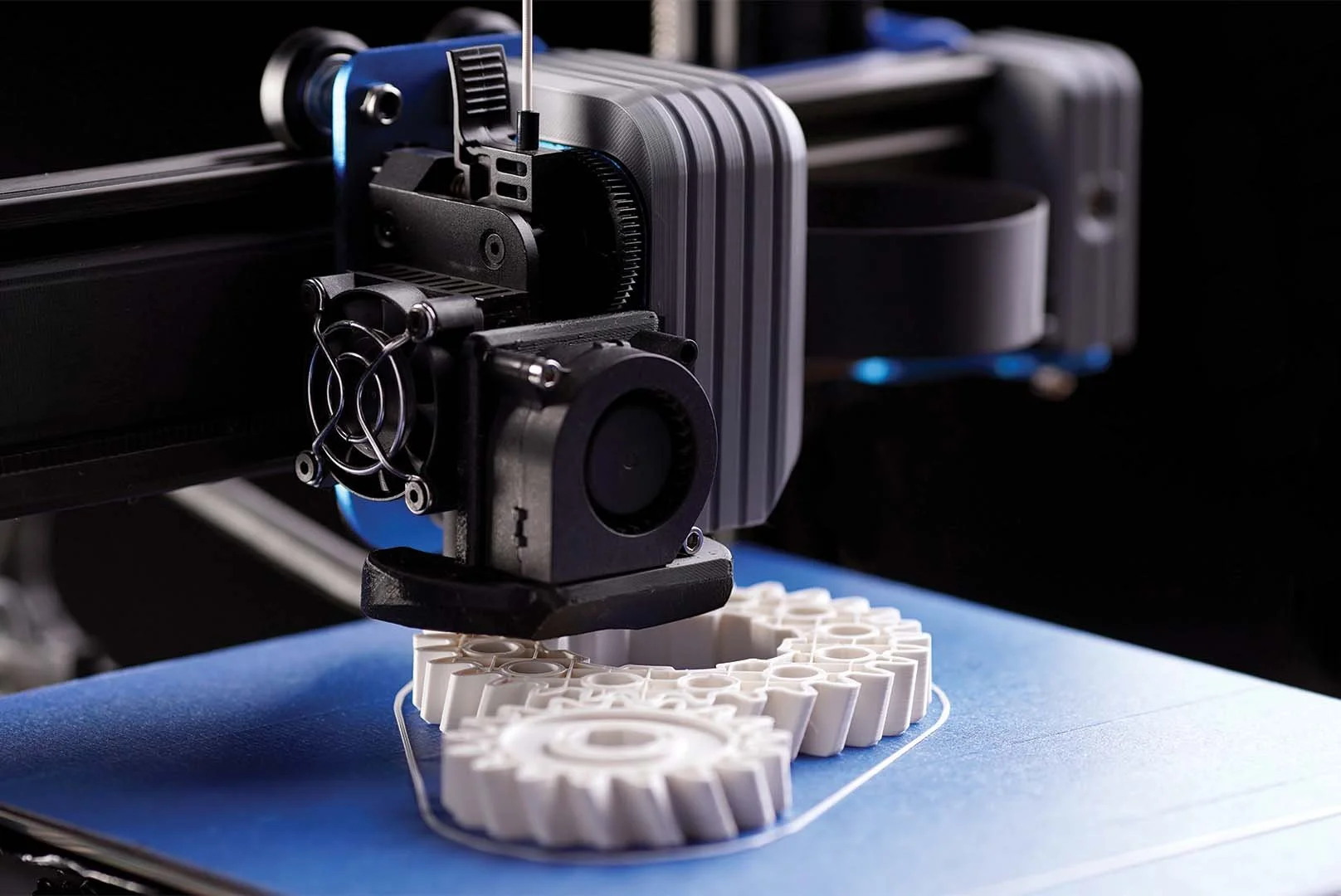

This innovative process, as explained by Shahrubudin et al., “creates physical objects from geometrical representation by successive addition of materials” (Shahrubudin et al. [1286]). The basic procedure is guided by a computer-aided design (CAD) program, allowing individuals to create 3D models of their intended design. This design is then sectioned into thin, horizontal segments by a “slicer” software, creating a set of instructions known as a g-code for the 3D printer. The g-code, used for Computer Numerical Control (CNC) operations, allows for the novel layer-by-layer construction of the desired design. While finalization of a design may include additive welding, powder binding, attachment of additional parts, or other processes, the basic steps for 3D printing are complete. With time to familiarize yourself with the software and tools involved in this process, 3D printing requires minimal time, exertion, and money, ideal for consumers and companies interested in savings and sustainability.

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, has recently been introduced to the field of construction, a driving force in the digitization and automation of this industry. 2 main types of additive manufacturing, powder-based systems and material extrusion, are utilized in construction. Powder-based systems involve the addition of powders to surfaces in thin-layers followed by a binder to solidify the structure, commonly utilizing “metal, ceramic, sand, polymers or mineral composites” as binders (“How 3D Printing”). Conversely, material extrusion constructs structures layer-by-layer by melting thermoplastic filaments and selectively depositing them on existing structures to solidify and fuse. These methods drive the success of the 5 printers most used in construction: contour crafting and concrete printing, which involve material extrusion, and selective binder activation, selective paste intrusion, and D-shape, which are powder-based systems (El-Sayegh et al.).

With the widespread potential of additive manufacturing for construction, it has become apparent that sustainable practices need implementation to create a more “green,” more environmentally conscious process. With construction “accounting for a staggering 37% of global emissions,” the ability to reduce waste, electricity use, and raw material overreliance is crucial to worldwide climate efforts and environmental preservation (“Building Materials”).

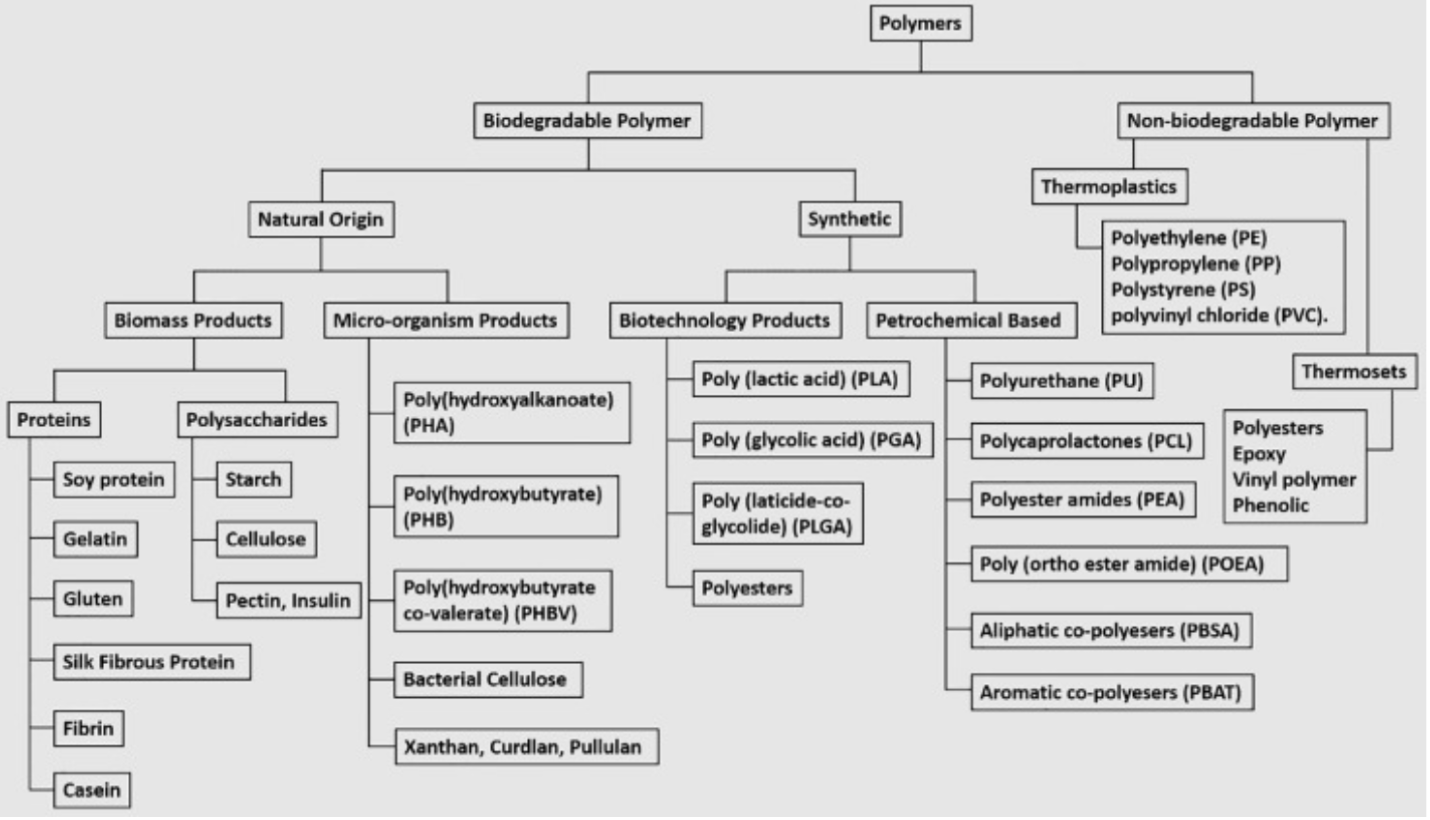

One primary means of addressing this crisis is the introduction of recycled polymers, specifically plastic, as a building material. For the purposes of additive manufacturing, plastic is lightweight and inexpensive, reacts well to typical finishing techniques, and decomposes without the need for an industrial composting facility. Globally, reusing polymers minimizes littering, potential harm to wildlife, microplastic contamination, and greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, recycled polymers have asserted themselves as a beneficial material, both for the sustainability of additive manufacturing and the betterment of global climate conditions.

Other materials have also been incorporated into 3D printing on construction sites. Bio-based materials, defined as materials solely or partly derived from natural biological sources, have become integral to 3D printing processes. While these can be composed from an array of substances, from cellulose-based materials to microbes to wood and bark, polylactic acid (PLA) has exerted itself as a primary material. Derived from corn starch or sugarcane, PLA is an eco-friendly option known for its biodegradability, recyclability, versatility, and ease (Djonyabe Habiba et al.). As such, PLA has become common within the field of additive manufacturing. Furthermore, advanced composites have also provided a means for using sustainable materials on construction sites. Examples include carbon fiber (CFRP) and reinforced polymers (FRPs), both of which have revolutionized construction materials. Known for a high strength-to-weight ratio, long lasting nature due to corrosion resistance, and design flexibility, CFRP and FRPs are both seen favorably within the additive manufacturing field.

In theory, sustainable building materials seem like the best potential option for the evolution of construction as a field. They are generally cost-effective, long-lasting, and environmentally conscious. However, the real question is their practicality and efficiency, primarily on construction speed, structural performance, and overall carbon footprint reduction. So, to what extent do these materials positively impact construction design and execution?

Firstly, the link between the use of sustainable materials and construction speed is rather complex. The complexity in this relationship lies in the fact that varying materials and varying purposes of 3D printed projects result in different influences of sustainable materials on speed. While some sustainable cementitious materials have been found to cure faster than normal cement products, other materials like PLA test at consistently higher cure times, thus taking longer to dry after heat exposure. This results in slight decreases or slight increases to construction time, respectively. Additionally, it is important to know that current 3D printing processes are built for non-sustainable materials. Current research is developing models specifically suited for recycled polymers, bio-based materials, and advanced composites, indicating decreases in construction speed will follow innovation to additive manufacturing technology itself. Overall, however, sustainable materials have not been found to substantially decrease or increase the time a construction process takes. The speed of 3D printing lies in the limited labor needs, automation, on-demand production and eliminated time-consuming assembly steps, making the influence of materials an interesting development to follow as the field progresses.

As for structural performances, researchers are finding that evolutions to sustainable materials increase their strength in comparison to typical building materials. While simple sustainable building materials, like recycled plastic polymers, are often characterized for high brittlessness, reinforcements to these substances have been found to have crucial structural and functional results. A biodegradable hybrid of bioplastic and PLA alongside carbon from waste coconut shells was found to have a 50% increase in tensile strength in comparison to bioplastic alone (Agrawal and Bhat). As such, hybrid components are becoming integral to the increase in structural stability of sustainable materials. However, other materials are still hugely successful. An example is CFRPs and FRPs, which are performing strongly in high stress fields, becoming commonplace in aerospace engineering, automotives, and ultimately construction. Overall, it has been found that sustainable materials either maintain, or in cases of reinforcement and hybridization, increase levels of structural stability in additive manufacturing construction processes.

Unfortunately, the link between additive manufacturing and overall carbon emissions is still an area of improvement. A study by Grazioso et al. found that additive manufacturing results in a carbon footprint “2 to 20 times higher per kilogram of material than” more traditional construction methods (Grazioso et al.). This carbon footprint is decreased when sustainable materials are utilized as energy requirements for the 3D printing technology is decreased. However, the benefits of limited waste production, extended lifetimes, and lessened transport energy expenditures have been the greater focus of sustainable energy use. This results in a process that is still more environmentally conscious than it was before implementation of sustainable materials, but still far from ideal for current environment goals.

Ultimately, 3D printing has revolutionized the field of construction. Minimized costs, increased efficiency, and accessibly, this adaptable technology is the future of countless industries. However, as a process plagued by higher carbon emissions, finding ways to minimize the climate implications of this technology is crucial to environmental preservation. By utilizing sustainable materials, specifically recycled polymers, bio-based materials, and advanced composites, overreliance on pure, natural materials and waste production can decline. Common criticisms, that these materials are significantly less effective, have been proven wrong. From a relatively constant construction speed across sustainable materials to potentially stronger structural materials when reinforcements are used, sustainable materials can be the future of this field. However, advancement can only be met with focuses on technology meant for sustainable material and continued efforts to minimize carbon emissions and environmental impacts from the technology itself. The future of 3D-printing is bright and its progress and evolution should be following in the upcoming years.

Works Cited

"3D Printing Industry Analysis." Fortune Business Insights, 17 Nov. 2025, www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/3d-printing-market-101902. Accessed 3 Dec. 2025.

Agrawal, Kavya, and Asrar Rafiq Bhat. "Advances in 3D Printing with Eco-friendly Materials: A Sustainable Approach to Manufacturing." RSC Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 6, 2025, pp. 2582-604, https://doi.org/10.1039/d4su00718b. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

Andrew, J. Jefferson, and H.N Dhakal. "Sustainable Biobased Composites for Advanced Applications: Recent Trends and Future Opportunities – a Critical Review." Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 7, Mar. 2022, p. 100220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100220. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

Djonyabe Habiba, Rachel, et al. "Exploring the Potential of Recycled Polymers for 3D Printing Applications: A Review." Materials, vol. 17, no. 12, 14 June 2024, p. 2915, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17122915. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

El-Sayegh, S., et al. "A Critical Review of 3D Printing in Construction: Benefits, Challenges, and Risks." Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, vol. 20, no. 2, 10 Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-020-00038-w. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

Graziosi, Serena, et al. "A Vision for Sustainable Additive Manufacturing." Nature Sustainability, vol. 7, no. 6, 1 Apr. 2024, pp. 698-705, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01313-x. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

"How 3D Printing Is Used in Construction." Kreo Software, 26 Mar. 2024, www.kreo.net/news-2d-takeoff/how-3d-printing-is-used-in-construction. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

Liu, Zhichao, et al. "Sustainability of 3D Printing: A Critical Review and Recommendations." ASME 2016 11th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, vol. 2, 27 Sept. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1115/MSEC2016-8618. Accessed 3 Dec. 2025.

Randolph, Susan A. "3D Printing: What Are the Hazards?" Workplace Health & Safety, vol. 66, no. 3, 5 Jan. 2018, p. 164, https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079917750408. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.

Shahrubudin, N., et al. "An Overview on 3D Printing Technology: Technological, Materials, and Applications." Procedia Manufacturing, vol. 35, 2019, pp. 1286-96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.06.089. Accessed 7 Dec. 2025.